How To Make Complex Tasks with AI Agents

AI Agent Implementation Rules

Hi there!

We’ve already published quite a few posts about AI agents, even though they only really started gaining traction the previous year.

Working with agents happens on a completely different level than chatting with a regular LLM model.

That’s why in this piece, we’ll break down:

What you actually need to know about AI agents

The rules that make them work (efficiently)

And which agents you can use today (and what they’re best suited for)

Let’s go!

From Tools to Agents

As we’ve already discussed, early AI tools had neither memory nor initiative. We were fully in control of every step of the process. The system did nothing unless something was instructed.

Later, with the rise of copilots, AI started to operate inside the workflow. We gained session-level context, reactive suggestions, and lightweight assistance, but there was still no real sense of intent or end goals. We’ve reviewed many of them before, and each is strong within its own niche: Notion AI, n8n, Zapier AI.

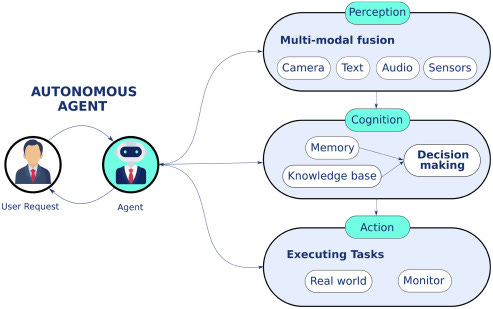

Today, however, the real challenge is the ability to act over time consistently and autonomously. And this looks like a job for AI agents. So far, AI agents can be defined as software systems designed to plan and execute tasks autonomously, make decisions, and interact with digital tools or environments with minimal human oversight (I’m sure that as agents develop, the definition will change).

This is why solving complex tasks has become the primary goal of agent development. Here is where things get interesting.

What is a Complex Task

Complexity emerges when a task requires sustained reasoning, adaptation, and coordination over time. I’d say the kind of processes professionals deal with daily.

Below are the characteristics that turn a simple task into a complex one for an AI agent.

Time framework

A task becomes compound when it operates over an extended period. Instead of producing a result in one session, the agent must track progress and remember prior decisions across days, weeks, and even months.

Multi-step dependencies

Later steps often depend on the successful outcome of earlier ones. An agent must plan and avoid taking actions that block future steps.

Tool and Environment switching

Many real-world tasks require an agent to operate across multiple tools, systems, or environments: databases, APIs, documents, browsers, internal dashboards, and code editors.

Need for self-correction

You know that errors are inevitable. What matters is whether the agent can notice that something went wrong and recover.

Partial observability

The agent never has access to the complete state of the task or environment at once. Due to this, information may be missing, delayed, hidden behind tools, or only revealed after certain actions are taken.

🧩 So basically, the core of any AI agent is based on three things:

Planning – figuring out goals and breaking them down

Action – actually doing stuff in the world (API calls, code, GUI clicks, whatever)

Critic – checking itself, spotting mistakes, and learning.

What we’re about to go through are pretty technical cases. They were originally written for devs, but the point is that you can totally use these rules for Vibe Coding too. It’s how you set up an agent so it gets exactly what you mean.

Scaling Long-Running Autonomous Coding

Cursor published an account of its experiments with running autonomous coding agents for extended periods. The goal was to test whether agent-based systems could handle projects that normally take human teams months to complete.

The experiments focused on three questions:

Can autonomous agents work productively for weeks?

How should multiple agents be coordinated on a single large codebase?

What breaks when scaling agentic coding systems?

Experiment Setup

Cursor ran hundreds of concurrent agents on a single project and deployed trillions of tokens with over one million lines of code. The system was designed to observe agents’ behavior in coordination, drift, failure modes, and recovery.

Step 1 – Testing the limits of a single agent

The team noticed that while a single agent performs well on well-scoped tasks, it becomes inefficient for large projects. In a nutshell, the progress is slow, context management degrades, and the agent struggles to reason across many interconnected components.

This led to the natural next step: parallelization.

Step 2 – Flat multi-agent coordination (it didn’t work, tho)

The first multi-agent design treated all agents as equals. Coordination was handled through a shared file where agents:

Checked what others were working on

Claimed tasks

Updated their status

To prevent conflicts, the team implemented locking mechanisms.

What failed:

Agents held locks too long, or even just failed to release them

Lock contention severely reduced throughput

In the end, everything went awry: agents failed mid-task, reacquired locks incorrectly, or bypassed locks entirely

The team then tried optimistic concurrency control and allowed free reads.

But with no hierarchy or ownership:

Agents avoided difficult tasks

Work skewed toward small, safe changes

No agent took responsibility for the end-to-end implementation

The result was churn without progress.

Step 3 – Introducing planners and workers

To address these issues, the team introduced new roles:

Planners

Continuously explored the codebase

Created and refined tasks

Spawned sub-planners for specific areas

Made planning itself parallel and recursive

Workers

Picked up assigned tasks

Focused only on execution

Did not coordinate with other workers

Pushed changes once tasks were complete

(And this worked out!)

At the end of each cycle, a judge agent evaluated whether to continue before restarting the loop.

Step 4 – Long-running experiments

Finally, using this architecture, the devs made Cursor run several large-scale experiments.

Building a Web Browser from Scratch

The agents ran for nearly a week, producing over one million lines of code across 1,000 files.

What mattered here was behavior:

New agents could understand the existing codebase and contribute

The system avoided collapse despite constant parallel writes and ongoing changes

Key takeaway:

With clear role separation and fresh planning cycles, agents can make forward progress on large codebases without shared global context.

In-Place Solid -> React Migration

Another experiment focused on long-horizon refactoring.

The agents performed an in-place migration from Solid to React in the Cursor codebase. The process spanned more than three weeks, with 266,000 edits made and 193,000 reverted.

Key takeaway:

Agents can handle large refactors when progress is continuously re-evaluated, BUT a user must still oversee at the end.

Product Performance Improvements

In a third experiment, a long-running agent focused on improving an upcoming product feature.

The agent rewrote video rendering in Rust and achieved a 25x performance improvement. It also added smooth zooming and panning, spring-based transitions, and motion blur that followed the cursor. This code was merged and prepared for production.

Key takeaway:

Given a clear goal, agents can deliver greater improvements that combine performance and user-facing behavior.

Key insights from the experiments

Model choice matters!

GPT-5.2 models performed significantly better at:

Sustained focus

Instruction following

Avoiding drift

Completing tasks fully

The team noticed that Opus 4.5 (which was billed as the best coding model in the world, by the way) tends to stop earlier and take shortcuts when convenient, yielding back control quickly instead of finishing tasks.

And it's not just them, I checked Reddit and found people discussing how newer Opus 4.5 versions seem worse than older ones!

The team also found that different models master different roles, using planners and workers with different model assignments.

Simpler systems scale better

The final system was simpler than expected. Workers handled conflicts effectively on their own.

Prompting is a core system component (nothing surprising)

Many improvements came not from infrastructure changes, but from classic prompt design:

It prevented pathological behaviors

Encouraged ownership

Maintained long-term focus

In practice, prompts mattered more than the orchestration framework itself.

What remains unsolved

The team notes several open challenges:

Planners should react dynamically when tasks are completed

Some agents run far longer than necessary

Periodic restarts are still needed to combat drift and tunnel vision

So, choosing the right model and designing effective prompts are way more important than complex infrastructure, as they drive task completion and proper behavior. Simpler systems with well-assigned roles often outperform over-engineered setups.

The team shared the implementation details if you want to go deeper: click

Designing a Travel Concierge with long-term memory using OpenAI Agents SDK

If the previous case was about setting up the agent, this case aims to show that multi-step tasks are only possible when an AI agent can use memory correctly: